|

Come, Tell Me How You Live: an archaeological memoir: Agatha Christie In Dartmouth for a few days, I decided to try the boat trip up the River Dart to Totnes and discovered that I could stop off at Greenway, Agatha Chistie’s family’s former summer home. Set high above and overlooking the Dart, Agatha bought it in 1938 and it is now a National trust property. I had never read an Agatha Christie book, not being a fan of crime fiction, but during the tour the guide mentioned a book I’d never heard of, Come, Tell Me How You Live: an architectural memoir, one of the few Christie non-fiction works and one of only two published under the name Agatha Christie Mallowan. Archaeological memoirs seemed a long way from crime fiction so, intrigued, I bought a copy in the bookshop. Mallowan was the name of Agatha’s second husband, Max, Christie being the name of her first husband. By now a successful writer, Agatha Christie was visiting archaeologist friends Leonard and Katharine Woolley who were to excavate a site at Ur, Iraq. She was researching material for a novel (Murder in Mesopotamia, published in 1936). It was her second visit and on their arrival at Ur the Woolleys detailed their young assistant archaeologist to be her guide. His name was Max Mallowan. He was 14 years Agatha’s junior, but the pair got on well. So much so that when Agatha’s return journey was planned and because Max was due a rest, his departure plans were revised so he could accompany her. It was this journey that cemented their relationship and they married later that year. The title, Come, Tell Me How You Live, includes a pun on the word Tell and comes from the verse A-sitting on a Tell with which the book opens. Tells, ancient city mounds, were the sites of the Woolley’s archaeological digs. The book was published in 1946, though she had the idea of writing it in 1938. However, she delayed starting it until around 1942 after Max had been posted to the British Council in Cairo. The notebooks, filled during several trips to Iraq and Syria with Max between 1934 and 1939, provided her material. The book’s chronology is confused, and she doesn’t mention dates. This is probably in the interests of brevity and to make the narrative more fluent; she was, after all, a novelist. She told her publisher the book would be “…not at all serious or archaeological” and described it as “…this meandering chronicle…”. Although Agatha had been interested in archaeology for some time, she had not visited any sites prior to meeting the Woolleys. Come, Tell Me How You Live is a book of its time and we should make allowances so as not to stand in the way of its enjoyment. There is some cultural stereotyping, as in her description of the comical ineptitude of the postmaster when the Christies collect their mail and get cash. She also attributes the attitude of some Arab workers to “the Oriental mind”. However, readers then would not have found this unusual: it is humour, not malice. At the same time, she is generous in her portrayals of the mixture of races she encounters. The Kurds; “men from over the Turkish border”; Armenians; Yezidis, whom she describes as “…so called devil-worshippers—gentle, melancholy-looking men, prone to be victimised by the others.” She is taken by the contrast between the Kurdish women who are “…gay and handsome…” and tall and wear colourful clothes; and the Arab women who are “invariably modest and retiring” and who “wear mostly black or dark colours”. While Kurdish men, she tells us, have “…the brick-red face, the big brown moustache, the blue eyes…”. Today we see how the catastrophe unfolding in Syria and Iraq has changed the lives of these people immeasurably. The Kurdish women now show their independence by forming formidable fighting units while the fate of the gentle Yezidis is almost beyond tragedy. There is poignancy in the place names, too. Agatha describes Palmyra’s “…charm—its slender creamy beauty rising up fantastically in the middle of hot sand”. Having been subjected to horrific modern-day iconoclasm, it has now been re-taken by Syrian government forces but much of its beauty is probably lost forever. She mentions a visit to Sinjar, where the world witnessed the suffering of the Yezidis, who had fled from the town and were trapped, starving on a mountain for weeks before being relieved. Raqqa, Homs, Der ez Zor and Mosul are also mentioned, names that now have a chilling resonance. Agatha’s introduces the cast of her “meandering chronicle” gradually as the story unfolds. Firstly Mac, the shy, introverted architect whose drawings provided a record of the digs. Another, known only as B, is there for additional support for Mac. He also provides one of the funniest episodes as he plays out the saga of his errant pyjamas. Then we hear of ‘The Colonel’ (Burns), a military man not an archaeologist who is detailed to supervise one of the digs while Max is engaged on another. He is a stickler for order. ‘Bumps’ (Louis Osman), also an architect, and then later in the narrative, Guilford Bell (no nickname for him), an Australian, also an architect and gifted artist (one of his drawings was used on the cover of Come, Tell me...). There are other characters, too, who support and accompany the archaeologists. The various drivers of their temperamental lorry Queen Mary—Aristide, Abdullah and Michel; their foreman, Hamoudi, and Dmitri, the cook. They provide many moments of humour often mingled with frustration. There is also the mostly un-named cast of workers who conduct the digs. They are portrayed much of the time as a quarrelsome rabble prone to fighting amongst themselves with varying degrees of violence causing much exasperation, mainly for Max. It must have been hard for a privileged middle-class woman—intrepid as she was—to endure the privations and discomfort of life in the desert, far from “the world where the electric light switch rules”. But a combination of humour and a British stoicism, keeps her going. It is unsurprising, though, that barely halfway through her narrative, she looks forward to her return, writing: “I begin to think of Devon, of red rocks and blue sea…It is lovely to be going home—my daughter, the dog, bowls of Devonshire cream, apples, bathing…I draw a sigh of ecstasy”. By December 1938 it was clear that it was time to leave as the clouds of unrest were gathering over Europe: “There is the feeling, this time, that we may not come back…” In her epilogue four years after leaving and when she has completed the book she says “…it has been a joy and refreshment to me to live those days again…in that gentle and fertile country…”. Come, Tell Me How You Live is a delight: engaging, funny and poignant, and a wonderful read but these are not characters found in one of her novels, they are real people, and when they are caricatured it is always with respect, humour and affection. Agatha Christie, Come, Tell Me How You Live (1946) Harper Collins × Pb × 205pp × £8.99 × ISBN 978-0-00-653114-2 Donald Oldham 2019 A version of this article was published in the Western Morning News on 4th August 2018.

0 Comments

It was blue, a sort of mid-blue. The chrome was a flaking and pitted, with rust spots showing through. But it was my first trike. This was early in 1948. It just appeared one day, presented to me by my father in an apologetic way. He told me it wasn’t new and that trikes are hard to come by and that he’d painted it for me. I may have said at some time that blue was my favourite colour, or it may have been that paint was scarce and that was the only colour he could get. I don’t know where he got the trike from; probably since the ‘30s it had been lying forgotten in someone’s shed. It hadn’t been handed over to make Spitfires, battleships or munitions and had reappeared when the owner was clearing out the shed and decided he had no further use for it, or perhaps he just needed the money. We moved to Scotland in 1943, a few months after I was born. My father had been invalided out of the navy and after rehabilitation he was sent to Scotland to do essential war work. We lived in a flat in Edinburgh at first, in Corstorphine, near the zoo, then we moved to the bungalow across the Firth in Burntisland. I don’t know if my parents had bought the bungalow or whether they rented it, they never told me. I spent a lot of time riding my trike back and forth on the poorly metalled road outside our bungalow. It was bumpy beneath the wheels of my trike. It may have been that the building programme was interrupted by the war and when the bungalows were built there was neither the time nor the materials to finish the road properly. Not long after I’d been given the trike my brother was born. It all happened in a calm manner; I remember no fuss. When the midwife arrived, I was in the sitting room and was asked to stay there till later. I’d been an only child for 5 years so was happy with my own company. There was a radio there but I didn’t know how to switch it on and, in any case, I don’t remember ever hearing anything of interest on it. There were some books that I could manage, some mine and some brought home from school. I remember reading and liked looking at the pictures in the encyclopaedias my parents had bought. I don’t remember learning to read and, as this was Scotland, I’d started school when I was just over three. Then there was a little bustle and I was called into my parents’ bedroom and shown this small baby. Everyone seemed pleased and I asked what he was called. They said Alexander Roderick, then they said he needs another name and I could choose one. I chose John and felt pleased. Alexander Roderick John sounded good to me. Then they said I could go. I left the bungalow and went out riding back and forth the along the road on my blue trike. It wasn’t long after that that my friend Innes disappeared. He was an only child and lived with his mother on one of the upper floors of a tall block of flats nearby. There had never been any mention of a father, Innes had only ever mentioned his mother. There were other children at school, too, who didn’t have a father. Killed in the war they often said. Someone told me that Innes’ mother had fallen from the balcony outside their flat. Innes stopped coming to school and I never saw him again. I suppose he either went to live with relatives or was placed in a children’s home. It made me feel sad but I don’t remember crying. I didn’t know enough then about these things but later, much later, I wondered if she just couldn’t cope and had ended it all. By 1948 the euphoria of victory had given way to a more realistic idea of what was needed to rebuild a nation battered by war. De-mob, although not complete, was well under way; rationing was to continue for some years yet, but in general there was a feeling things were beginning to recover. We had a car now, a 1938 Ford 8. A year or so later, my father was released from the necessity to contribute to the war effort and was able to look for work elsewhere. Eventually, he found another job, not in Scotland but in Taunton, Somerset and we were to live in Wellington. When the time came to move the plan was that I should accompany my father in the car while my infant brother would travel by train with my mother. We were to stop off in Ashton-under-Lyne near Manchester (where I was born) to break the journey, stay with my grandmother and proceed the next day. The car had no heater, only 3 gears and a top speed of around 60mph. I don’t recall much of the journey, which is perhaps as well. All this was in the future, but I can still remember that early spring day in Scotland when I was given a brother, and my new blue trike. ©Don Oldham 2018 A version of this memoir was published in the Western Morning News on 14th July 2018. Primo Levi published The Periodic Table (Il Sistema Periodico) in 1975 in Italian, and in English in 1985. This being some years after he had published If This is a Man and its sequel The Truce, his accounts of his incarceration in Auschwitz. The Periodic Table is a masterpiece. It is a collection of 21 reflections, each named after a chemical element. Levi doesn’t tell us why he chose the elements he did but he transforms the properties of each into an extraordinary personal narrative. He says of it ‘...this is not a chemical treatise…Nor is it an autobiography…but it is in some fashion a history.’ The Royal Institution of Great Britain placed it on their short-list of the best science books ever written and it must be required reading for every undergraduate chemistry course. Levi was a chemist, novelist, poet, memoirist, and Shoah survivor¾ a giant of post WW2 Italian literature. He never confined himself to any of these categories and had continued to work as a chemist alongside his writing career until he retired from the paint factory he managed, in 1974. However, The Periodic Table is one work in which he manages to draw on all the disparate experiences of a rich, varied and traumatic life. In Argon, he reflects on his family and his Jewishness; in Zinc, the poignancy of young love. Iron, tells of his friend Sandro Delmastro: ‘…a loner…he had an elusive, untamed quality…’ Sandro, educated and a voracious reader who, at the same time, was at home hiking in the mountains and who became self-sufficient in the wild. Through his friendship with Sandro Levi also learned many of these survival skills; skills that were to be useful when they both—though not together—joined the resistance. However, skilled though they were they were unable to avoid capture. Tragically, Sandro was shot in the back of the neck by a burst of sub-machine gun fire while attempting to escape from his Fascist captors, while Levi was eventually sent to Auschwitz. In Vanadium Levi describes a chilling re-encounter with a Dr Müller, a fellow chemist who had charge of the laboratory in Auschwitz to which Levi had been assigned. But what drew me to TPT is Levi’s humanity and the way he deals with the bitterness he must have felt as a survivor of one of the worst episodes of genocide in history. I do wonder, though, about the label ‘survivor’ attaching to a someone who eventually took his own life. It’s beyond doubt that much of the trauma of Auschwitz will have haunted him and we know he suffered from bouts of serious depression that started in 1963. His death after a fall in 1987 was recorded as suicide, though there are some who doubt it and claim it was an accident. However, of all these remarkable ‘histories’, Carbon is the tour de force. This is the work that seems to anticipate the growing awareness among environmentalists of the impact inherent in the carbon-based economies of the developed world. ‘I wanted to tell the story of an atom of carbon,’ Levi tells us. And in just a few pages, he liberates an atom of carbon from its long imprisonment with oxygen and calcium in limestone and elevates it to the ‘element of life’. So begins the remarkable story of the journey of an atom through time and space; through the mystery of life and death; though it is transformed it is never destroyed. At the same time, he is leading us on a journey through the imagination of a great writer. He begins in a notional 1840, when a pickaxe-wielding labourer detaches his atom of carbon from a rock. It is kilned and starts its journey into and through the ‘world of things that change.’ It is inhaled and exhaled; dissolved and expelled; moved by the tides and blown by the winds until, once more in captivity, it embarks on what Levi calls ‘the organic adventure.’ Our atom finds a temporary place to rest in a leaf before undergoing the miracle of photosynthesis only finally to become part of that ‘impurity’ that itself threatens life on our planet—carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas. And in his final magnificent paragraph Levi describes how it will then be swallowed ‘in a glass of milk’ and be incorporated in a long chemical chain that will be broken down yet again. It will move from our bloodstream; it will ‘knock at the door of a nerve cell’; it ‘belongs to a brain’, his brain as the writer, now ours as readers. But its journey is not over; it will never be over, it cannot be destroyed. Once a part of us, then part of what we will become; part of what we will leave behind us when we are gone, when there’s nothing of us, not even ‘…this dot, here, this one.’ Primo Levi, The Periodic Table (2000) Penguin . Pb . 195pp . ISBN 0-14-118514-7 ©Don Oldham 2019 Estuary I (Woodpeckers) Winter sun lay warm on our backs. The grass greened by the rainstorm still wet as a tear. From a leafless copse came a rapid knock unechoed across the softening air. And then the quiet. But a shy rebuke, a distant tap, faint compromised the calm. II There in his cassock that sepia boy, unsmiling—prayer book, cathedral glow behind. In his eye a pale not-quite stare, uncurious. Why was he there? Now he’s in the grass and in the air, somewhere deep, deep in the sand, deeper in the rock. III It winds through the walls, through different grasses, slowly it uncoils itself to a flow towards the marshes creeping only by the smallest measures gravity allows; short of the beaches finally to lie on the dry reaches ignored by the gulls. IV The darkening sky, the gathering squall; all of yesterday the air was alive; now storm waters fill the waiting floodplain, coursing down until the weaker banks give. This is where tidal meets estuarine carrying reddle into the wild sea. V With a heavy heart I took Fore Street Hill. From the deep twilight casting its grace song out over the still air, a hidden bird. I listened until calmed—but not for long; things became less clear, dumbed and sequestered in Mackerel Square with a heavy heart. VI February and a late leaf dances on the morning wind. Moving air stalls frost but there are dry fields where warmer air goes, there among the shards we believe were lost but are just hidden beneath the shadows with the forgotten and the abandoned. VII Clamorous gulls call out on the night air; the slowing waves fall on ancient pebbles; a curve of moon there half-hidden by cloud low above cliffs where by day gulls squabble. Dreams end here because we now hear aloud our deepest thought as murmurs on the swell. Other poems

The wind The weather forecast says the wind turned; it comes from the east today. This weather was yours yesterday. The molecules that make this moving air have chilled your skin, stroked your hair. I turn my face to the wind and through its chill your warmth is there. The Storm The slow build up to the storm deceived me. The still air lay heavy on the roof. The roof supported it. I was unmoved. Though apart we were each enclosed. Then the other air came. It moved off the ocean, soft breath gathered up into a roar. Not a hat wind, a chair or a table wind - more. It assailed the roof. So strong that on the ridge the flashing lifted. So strong that the terra cotta finial, blown from the pediment, fell and smashed slates slid. The world tilted. The promise We didn’t start with a promise. It seemed understood. Anyway, what could we promise we hadn’t promised to others before? It would have seemed like empty renewal to say the same again. We lived an unspoken promise. Moving Out I used to think all we had was here, at home, contained. But you gradually moved out parts of yourself like belongings; books lent and not returned. The Rescue I’d given up shouting, reconciled to being alone. Trying to be ready; trying to get the breathing right. Not too loud, so I’d hear if you came. It was hours before they came. The Roof The roof held. Through last year’s storms it held good. Others’ didn’t. Tiles were displaced, some fell; must have leaked too. This one was sound though: sound enough, I thought. Wasps wouldn’t nest in unsound eaves. It would need to be dry for them. They were nesting when we first summered here and we had to kill them. Sometimes I can still hear their buzz in the dry air. Burial in the rain Rain. The rain none wanted; not the farmers whose hay lay in the fields to dry; nor we, gathered here as we mumbled our goodbyes. The earth’s silent embrace waited. But there is no sure and certain hope, no mercy here, just birdsong and flowers and mute trees and the rain, still the rain. This is a book about a cricket match. Now I realise that will sound unpromising to anyone who is not a devoted fan of this great game. I am and so is David Kynaston, so bear with me, it’s more than just that. For a while now I’ve been an admirer of David Kynaston, the social historian who more than any other makes me feel he’s speaking directly to me. His magisterial history of Britain, Tales of a New Jerusalem from 1945 to 1979 is up to four volumes to date with the promise of more. What drew me to this study was that I wanted to know more about the world in which my parents were raising me, a war baby. I grew up with the new welfare state that the pioneering Labour government—following its landslide election victory of 1945—introduced, its shining example being the NHS. This great institution gave me vitamin enriched orange juice and vaccinations and continued my father’s rehabilitation; he’d been invalided out of the navy. On looking through Kynaston’s impressive list of publications, which includes his recent four volume (yes, again) history of the City of London as well as other heavy tomes, I was drawn to three intriguing titles all about cricket and I ordered one. When I collected WG’s Birthday Party I was almost disappointed to see that unlike most of his other books, it’s a slim volume, too slim as it turned out because it is a joy. Funny, packed with the kind of detail any cricket lover would appreciate; and poignant as well. But, as I said, it’s more than that. Kynaston’s primary sources in Tales was the Mass Observation Project. Observers were appointed, anonymously, to record the conversations of people, in public places; pubs, clubs or in other places where they gathered. These voices were not those of the historians nor of those in power but of ordinary folk. He then uses this information to tell stories. And this small gem of a book is a story, too, but about cricket in the last few years of the Victorian era and one of its greatest figures. Wherever the game of cricket is played, the name W.G. Grace will resound. In 1898 W.G. Grace, England’s foremost cricketer and by this time a legend in the game, would reach the age of fifty. To celebrate this the cricket authorities decided that the Gentlemen v Players match of that year would be rescheduled to start on the great man’s birthday. For cricket fans, this match was the fixture of the season. Test matches were infrequent, the county game in its infancy and the distinction between the Gentlemen (amateurs, usually from a privileged background) and Players (professionals, usually from more humble origins) was well defined. On the score cards the Gentlemen were allowed their initials and military ranks while for the Players it was surnames only; Players addressed the Gentlemen as ‘sir’ but again the Players were just surnames. W.G., as a qualified medical practitioner, was regarded as an amateur. No doubt today we would describe him as a ‘shamateur’; he amassed a comparative fortune from cricket and was notorious for his moneymaking acumen. In telling us the story of this unique fixture Kynaston also tells us about how social class played such a part, as well. A bit of history: the fixture was first played in 1819 and the gulf in ability between the Gentlemen and the Players was stark. For many years the professionals prevailed including one notable match where it was arranged that the Players should defend four stumps each nine inches taller than usual. Despite this it was a rout. The Players only needing to bat once while the Gentlemen’s second innings amassed a mere 35 runs and the top scorer, with eight, was one Roger Kynaston (a relative?) who went on the become an MCC Secretary. But back to this fixture. D. Kynaston takes us through all three days of this celebratory match one at a time; the weather (which, this being England, played its part); the crowds and the players—the inter- and intra-team rivalries—and paints a detailed picture of the ebbs and flows of a memorable occasion. And above it all—it was after all his birthday—looms the towering figure of W.G. but there were other characters who played their parts and other stories to tell. The Gentlemen had Capt. E.G. ‘Teddy’ Wynyard, a Boys’ Own hero if ever there was one: A career soldier who had won the DSO…he was a man of many parts: in the Old Carthusian team that won the FA Cup in 1881; a prominent rugby and hockey player; an excellent figure skater; tobogganing champion of Europe in 1894; and recipient of the Humane Society’s medal after rescuing a Swiss peasant from under the ice on the lake at Davos. But he won his greatest renown on the cricket field… And Andrew Stoddart, ‘…in every sense one of the most attractive cricketers of the day…an almost complete batsman…’ who opened the batting with W.G. The Gentlemen also had other double internationals; the all-rounder Johnny Dixon also represented England at football; and Samuel “Sammy” Woods was a rugby international dubbed ‘…the Father of Modern Wing Forward Play...”. And on the other side of the Class divide the Players had their stars, too. Arthur Shrewsbury probably the best batsman in the country between the mid-1880s and mid-1890s. Lord Harris, not one given to extravagant praise for Players regarded an innings of Arthur’s against Australia on a rain affected track, overcoming Fred Spofforth, “The Demon Bowler’ as ‘...the finest innings I ever saw…’. Shrewsbury’s opening partner, William Gunn was also a double international, appearing for England at football. He went on to start the sports equipment and clothing company Gunn & Moore, still operating today. However, despite several eccentric omissions by the selectors—Ranji, Fry and Jessop—the Gentlemen were likely to be formidable opponents. By now W.G.’s record, even judging by today’s standards where much more cricket is played, was extraordinary. If not a giant physically, he was a large man, around 18 stone in his later years. Yet who would have known now that also his attention to personal hygiene was less than fastidious; his soft Gloucestershire burr was delivered in a high-pitched, even squeaky voice and his commitment to the fair play inherent in this great game was not always evident. Perhaps not exactly a cheat, he was at least an infamous manipulator (or intimidator) of umpires. There are many examples of his using all the means at his disposal to have decisions changed to his own advantage. Inevitably, it was W.G.’s day but he didn’t have the stage all to himself. Cricket is a team game, but it also embodies a contest between bat and ball that leaves plenty of opportunity for individual, sometimes match-winning contributions. And this game was no exception, there were some virtuoso performances both from the Gentlemen and the Players. There was the fearsome pace of Kortright, the fast bowler; the power and flair of Gunn’s batting; the—at times—unplayable ‘turn’ from Hearne J.T. (his brother Hearne A. also played hence they were allowed their initials); and, inevitably, the contribution of the great man himself, W.G. The game, as Kynaston noted, ‘…transcended any set of statistics, for virtually all who saw W.G.’s jubilee match were certain that it would live in the memory.” Within the next three years the 19th century gave way to the 20th and the death of the old Queen brought the Victorian era to an end. The brief lull of the Edwardian period saw the careers of many of the cricketers continue, both internationally and in the county game, until retirement. W.G. played on, finally bringing his First Class playing days to an end after scoring 74 at the Oval on his 58th birthday, though he continued to make appearances in club games. Then in 1914 the catastrophe of Great War was loosed on the world. Several of those who played in this match were young enough to fight and here Kynaston strikes a more poignant note. Some perished in the war and some survived. The mercurial Stoddart took his own life. Also in 1914 W.G himself died after a series of strokes. Both during and after the war several of the Players found it hard to make much of a living when their playing days were over but some fared better—Gunn’s sports equipment company still bears his name even though the ownership has changed. While the last of the cricketers who played in the jubilee match died in 1958, Walter Rhodes, who, as 12th man fielded for both sides but didn’t appear on the scorecard, lived on until 1973. Cricket has never been insulated from the wider forces at work in society but the dramatic changes during the period following WW2 (an area of special interest for Kynaston) was, perhaps the end of a kind of golden era in the game. The Gentlemen vs Players match struggled on until the sponsorship of a new form of the game was agreed by the cricket authorities, the limited overs contest. The abolition of amateur status followed and together these sounded its death knell in 1962 and the fixture was no more. This gem of a book is more than just a fascinating story for cricket lovers told with humour and sometimes pathos by a true lover of this sport. Yes, it is an account of a memorable occasion in honour of one of the giants of the game, but it also records what was one of the last hurrahs of the Victorian era. WG’s Birthday Party, David Kynaston, Bloomsbury, 2011 ISBN 978-1-4088-1208-2 ©Don Oldham 2019

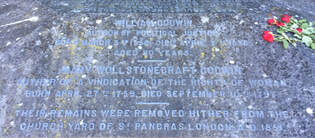

He arrived in London in July 1862 carrying a return ticket between Dorchester and Paddington (just in case) and two letters of introduction to London architects, one of them by his father. One of his letters resulted in his being referred to Blomfield’s, an architectural practice, one of whose specialities was ecclesiastical renovation. His prior experience in this field when at Hicks’ must have counted much in his favour and he started at Blomfield’s office in St Martin’s Place just off Trafalgar square in the first week of May 1867. Arthur Blomfield was one of the most successful architects in London. A young—he was 33—and fashionable figure, a member of the establishment, well educated, good at sport and President of the Architectural Association; he must have impressed Hardy greatly. Even though his friendship with Horace Moule in Dorchester had introduced Hardy to a new and different intellectual world, he still must have felt provincial and out of place in his new urbane and metropolitan milieu. The practice comprised Blomfield, six articled pupils, perhaps three assistants, and Hardy and it wasn’t long before Blomfield recommended his new and promising pupil for membership of the AA. At this time the building of Midland railway line into St Pancras station was under way and involved much disruption to the surrounding area. The new line was to cross several churchyards and Blomfield was engaged to oversee the exhumation and reburial of the occupants of the many graves affected. The Bishop of London had been disturbed that previous exhumations had not been conducted with due dignity and consideration. There had been grisly rumours that bags of bones had been sold to bone mills. Blomfield was the son of a late Bishop of London and the current Bishop charged Blomfield with the task of ensuring that further exhumations were carried out in a proper manner. St Pancras parish church, next on the list, was one of the oldest sites of worship in London. Indeed, during earlier excavations remains of a Roman building (probably a temple) had been discovered. Blomfield had no hesitation in appointing his new employee to oversee the exhumations, paying not only planned regular visits but also unannounced ones. The work was to be conducted at night under lamplight. During one of Hardy’s calls he was shown a broken coffin in which there was one skeleton but two skulls. Biographers have noted the many mentions of churchyards and graves in Hardy’s work and how important they often are, so this find must have appealed greatly to Hardy’s sense of the macabre and the incident clearly stayed with him. Fifteen years later the by then established literary figure was reintroduced to Blomfield whose first words to Hardy were: “Do you remember how we found the man with two heads at St Pancras?” and their friendship was reignited. There were also sensitivities surrounding the exhumations as there were buried there several well-known figures, among them the architect Sir John Soane, J. C. (the “English”) Bach and Mary Shelley’s parents, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, whose monument was still there although Mary had already had their remains moved. They were reinterred in a churchyard in Bournemouth. She and Percy Bysshe Shelley used to meet in St Pancras churchyard in secret when they were courting, seated by her parents’ grave.  The grave of the Wollstonecraft/Godwins, St Peter's Church, Bournemouth. Percy Bysshe Shelly's heart is also buried there Hardy got on with the task, but the problem emerged as to what best to do with the headstones as they could not realistically be kept with the reburied remains, and in any case the churchyard was to be turned into a public park. It’s not clear whose idea it was—probably Hardy’s—but the headstones were gathered close together and in an upright position around the base of a nearby tree.  Gravestones incorporated into the base of The Hardy Tree, Old St Pancras churchyard, London Over time the tree growth has incorporated the closest stones and they are now embedded in the trunk, a form of inosculation. So here, in a churchyard, among the apartment blocks, close to a large in inner-city hospital is an almost forgotten memorial to one of our greatest novelists and portrayers of west country rural life.

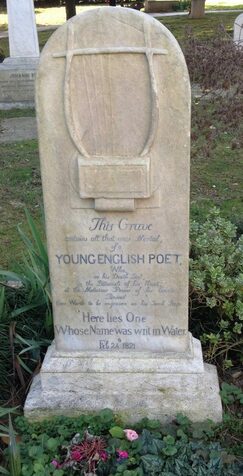

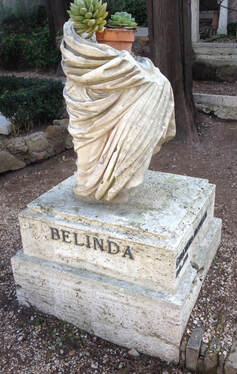

John Keats is buried in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome (Known also as the Cimitero acattolico or the Campo Cestio Cemetery). I knew that. One way and another, Keats has been with me since I first became interested in poetry. A few months after visiting the Keats House in Hampstead, I was in Rome, making plans to visit the house by the Spanish Steps where he lived for a short while and where he died. I also intended to visit his grave. It was from Wentworth Place (now the Keats House) that Keats set out in September 1820, accompanied by his friend the painter Joseph Severn, to Rome on what was to be his final journey. He was seeking some relief in the kinder Roman climate but as a doctor he knew he was desperately ill and that death could not be far away. A tortuous passage, poor weather and an enforced quarantine in Naples meant they didn’t arrive in Rome until November, so missing the best of the weather. This, coupled with the ministrations of a Dr James Clark with his good but misguided intentions, did little but hasten Keats’ end. Joseph Severn had agreed to travel with Keats, though up until then he had been only an acquaintance. However, he quickly became a good friend and a dedicated nurse, and it was in Severn’s kind arms that Keats died on 23rdFebruary 1821. He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery and had left instructions that his headstone should bear no name nor date. However, Severn, together with Charles Brown (a mutual friend), decided to add, under a relief of a lyre with broken strings, the now famous legend, Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water It was not until this visit that I realised how many other stories this fascinating place has to tell. And it was the point at which I realised that this is more than a protestant cemetery; buried there are people of many religions and none: Orthodox and other denominations of Christians; Jews; Muslims; Zoroastrians; Buddhists; Atheists. I’d gone there on a Keats pilgrimage but found myself listening to many other voices. Shelley—who, when he drowned off the coast of Tuscany and his body cremated there on the beach had his remains (minus his heart, which resides in the crypt of a Bournemouth church) interred here. While his body was being prepared for the pyre a small volume of Keats’ verse was found in his pocket. Edward Trelawney, a friend of Shelley’s had the ashes exhumed and reburied in a more favourable site near an ancient wall and marked by a tomb stone with the legend Cor Cordium—Heart of Hearts.Close to Shelly’s grave is that of the American ‘Beat’ poet, Gregory Corso, buried there at his request. The Italian political thinker Gramsci lies here, as does Goethe’s only son. This is an extraordinary place: to wander here—among the famous and the not so famous; between the grandiose and the understated; the proud and the modest; with the forgotten, the half-remembered and the celebrated—is to be with a silent crowd. Many of those buried here have travelled the world to end here. One sarcophagus, however, has in a sense returned itself to the world: Angel of Grief.  This sculpture by William Wetmore Story serves as the gravestone of both the sculptor and his wife. It has become a widely recognised piece of modern funereal art and has been reproduced in one form or another in cemeteries across the world: from Canada to Cuba, from the United Kingdom to the United States.  However, an unexpected find for me was the grave of a British actress I remember from my adolescence, Belinda Lee. A neighbour had told me she was born in Budleigh Salterton, Devon to a hotel-owning family and spent her childhood there in a cottage overlooking the red cliffs of this small, genteel coastal town. But I wanted to know why she was buried here in this extraordinary place and how that came about. Belinda Lee went to RADA where she was spotted and signed by Rank Studios. She soon graduated from her early demure rôles to playing ‘sexy blondes’ in lightweight British productions. She was married briefly to a photographer, Cornel Lucas but when the union started to crumble she moved to Italy. There she managed to escape playing ‘sexpots’ in more Frankie Howerd and Benny Hill films, nevertheless, she was still cast as a voluptuous temptress albeit in more dramatic productions. It was in Rome that she embarked on a much-publicised affair with an Italian Papal Prince while they were both still married to others. They both survived alleged suicide attempts only for her to perish in a car crash in California shortly after: she was not yet 26. And this is where her ashes are interred, in the Protestant Cemetery in a grave bearing the simple legend ‘BELINDA’. An extraordinary life for a young woman from the town where I now live. There are people here who still recall the family, fewer, though, who remember the remarkable trajectory of the brief, tragic life of this beautiful young woman: from Budleigh Salterton to London and then to Rome; to California and then on her final journey, back to Rome, to the Protestant Cemetery. And so it was: I’d travelled to Rome with the spirit of John Keats only to return with the ghost of Belinda Lee, to the town where I live, the town where she was born. © Don Oldham 2018 A version of this post was published in the Western Morning News on 8th September 2018. Last year I was lucky enough to interview abstract painter Liz Cleves as she was preparing work for her upcoming exhibition at the Penwith Gallery, St Ives, from 5th March to 8th April 2019.

THE BIG POND: an interview with abstract painter Liz Cleves. Liz is an abstract painter living and working in Budleigh Salterton. Originally from Cornwall, she retired from teaching and resumed painting—which had always been a passion—concentrating initially on landscape. More recently, though, Liz found a new creative direction and turned, successfully to abstract painting. She has had work shown in several exhibitions including a successful one-woman show at the Woodhayes Gallery. I caught up with Liz as she was preparing work for a forthcoming exhibition in the Penwith Gallery, St Ives. What do you think makes an artist? Everyone can be take up the invitation to be an artist of some sort. By that I mean that…. everyone can essentially be an artist - an entirely new and unique artist indeed. I believe that it is an essential aspect of being a ‘creative being’ that we find the ‘creative centre’ of our lives and explore that in its uniqueness. I don’t think that being creative is at all easy. Because being true to one’s self and exploring the contents of one’s own life - one’s own experience; one’s particular way of looking; one’s motivation and feeling - requires resolution and dedication. And because of that one has, at times, to neglect the opinions and persuasions of others. You showed me your painting The Big Pond and you told me it signaled a move from your earlier style as a successful landscape and representational painter to an abstract one. What was behind this? I find it hard to respond to being asked about why I do what I do, without sounding strangely out of kilter with life as others seem to see it. I am often asked by people why I don’t paint the world as they see it. When I can paint perfectly ‘normal’ scenes from the visual world, why would I paint something that is difficult for others to relate to; to give purpose and reason to? Why on earth do I put myself in the strange and ‘unaccompanied’ position on a quest for recording some new, and previously undiscovered ways of expressing colour and form? I do know though, that I paint what is important in my mind. What are the important elements in abstract art, given that you’re not trying to represent things in the ‘real’ world? I mean, where does colour fit in, for example? Colour gives such a sense of jubilation: to stroke it on to canvas and watch what it does to the rest of the canvas; laying on a colour and another colour and maybe another, too. It is an adventure into the unknown. The uncharted surfaces of the brain are as unimagined as planets in other solar systems. So why not go there? Why not? Go, and see what can be conjured up! Is form secondary, then? I paint form and I think, importantly, about the relationship of each of those forms—in itself and in relationship to the whole composition. However, colour affects form and form colour. Only by trying the two together does one get a sense of what might then occur. For sure there will be a dynamic created. It is safe to try this and try I must. So colour and form are equally important. Colour in my work comes from a huge kaleidoscope of colour memories and ideas that have been stored in some unfathomed part of my brain over a lifetime of looking. (I remember colours from when I was little and I treasure them like others do jewels). Shapes come into my work as a result of shapes I have seen somewhere, at some time. The references tend to be plants seascapes and built environments. But also forms come from a sense of ‘feeling’ of how things are; from moving, and listening, and looking—and being still. What about the process of painting? It is easy to paint away at a work and neglect to stand back and get ‘the bigger picture’. Often time away from the work is well spent as thoughts regarding form develop in one’s head. It is after such times that a return to work may offer fresh inspiration. I believe it was the French poet Valéry who said something like “A poem is never finished, merely abandoned.” So, when to stop? When is the picture ‘done’? Here is a tantalizing issue that crops up regularly in conversations between artists. Often artists have ‘an idea’ of when to stop work, but they may, at a later time, review progress and begin work again, having seen things that might be added or modified. Do you ever feel you are overdoing it? Spending too much time on a particular work? One gets a sinking feeling at times when it is evident that too much work or too much thinking has been done on a picture. The result perhaps of applying too much paint; having a seemingly unresolvable problem with composition; or loss of inspiration for the piece. One might admit that nothing can be done, though on occasions the situation can be turned around. Is this, perhaps, only difficult with an abstract painting? The solution for finishing a piece of 2 Dimensional ‘figurative’ work is usually more obvious than with more abstract pieces. Probably (though not exclusively) because it is easier to see when a figurative piece matches the material it is intended to represent). Liz has accumulated a substantial body of impressive work now and submitted some paintings to the Penwith Gallery, St Ives. During her earlier life in Cornwall, Liz had visited the gallery many times. She had always hoped that one day that she could exhibit there, in the gallery where many of the artists important to her had shown: Hepworth, Frost, Barns-Graham among them. She was delighted to learn that her work had been accepted and Liz is now preparing some new work for the exhibition scheduled for 2019. ©2018 Don Oldham In the summer of 1819 a moderately successful landscape painter and his ailing wife took a small cottage in Hampstead, then a village to the north of London. The couple were looking for more amenable summer surroundings than their house in Charlotte Street, central London offered, hoping this would contribute to an improvement in her health. They took tenancy of Albion Cottage in what was to be the first of their summer migrations...

|

Don Oldham's BlogArchives

December 2019

Categories |

||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed